What they are, where they come from, and how ALPLA is helping reduce their impact

Cutting through the confusion about microplastics

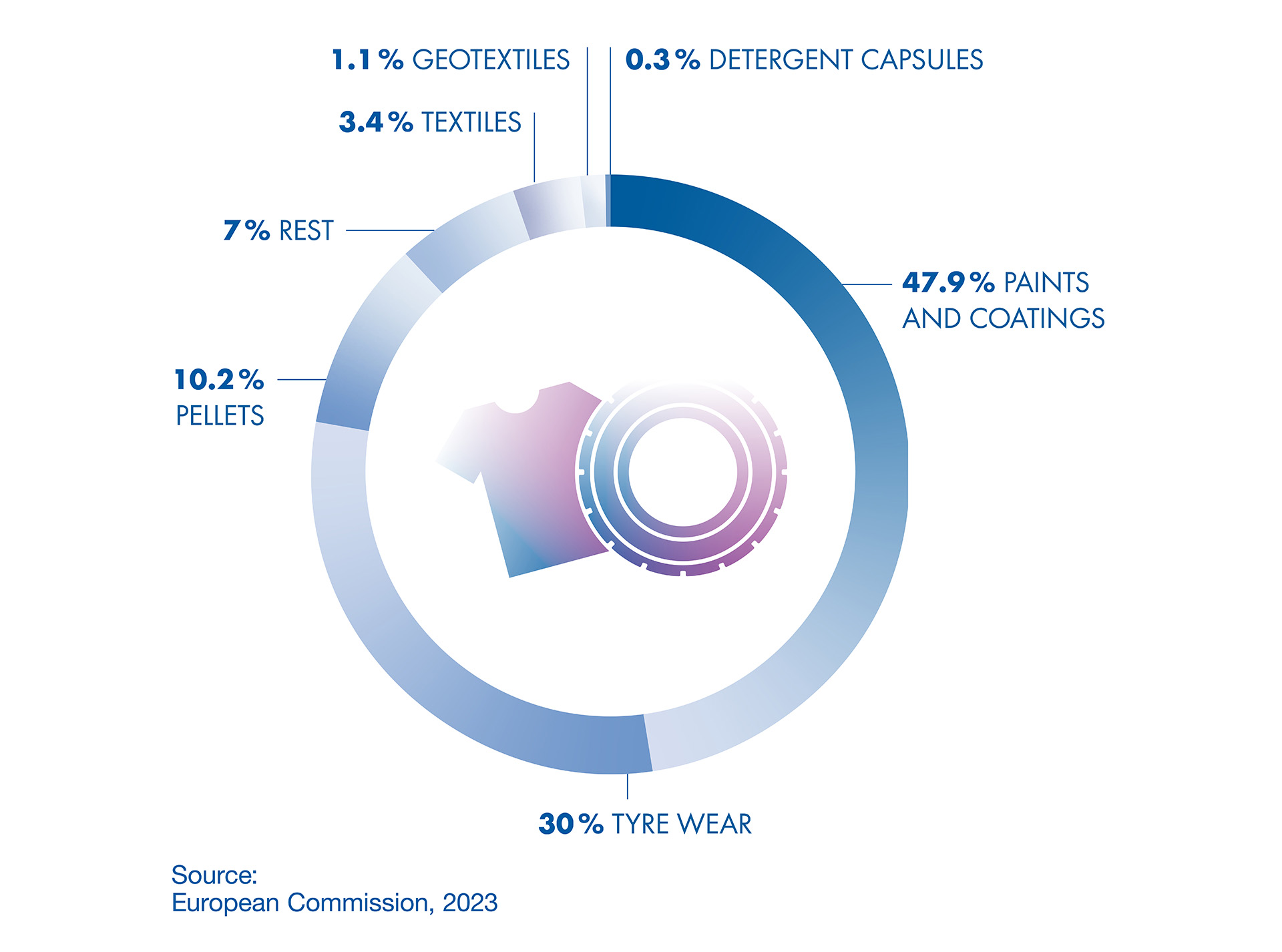

There is a great deal of half-knowledge in circulation on the topic of microplastics. It is claimed, for example, that plastic packaging is its primary cause. But it is a little-known fact that the primary sources of the unintended release of microplastics are paints and tyre wear. We have therefore compiled the most important information from scientific sources below.

What Are Microplastics and Nanoplastics?

According to a broad definition by the ECHA (European Chemicals Agency of the EU), microplastics include all synthetic polymer particles smaller than 5 millimeters that are organic, insoluble and shear degradable. Nanoplastics are solid particles of synthetic or heavily modified natural polymers with sizes between 1 nm and 1000 nm, although some authors have suggested an upper limit of 100 nm, as for engineered nanomaterials.

Primary vs. Secondary Microplastics: What's the Difference?

As of now, there is no universally accepted legal definition for primary and secondary microplastics across all jurisdictions. However, some regulatory bodies and scientific communities have provided definitions and distinctions to help guide policies, research, and management efforts related to microplastics.

The key difference lies in how they are created. Primary microplastics are produced by design at a small size, while secondary microplastics result from the breakdown of larger plastics objectives. Additionally, there are the terms “intentionally added microplastics” and “non-intentionally added microplastics”. In the EU, the term “intentionally added microplastics” is legally recognized, particularly in relation to products like cosmetics and cleaning agents.

Sources of Microplastics in the Environment

Microplastics enter the environment from many different sources. Figures from the EU Commission's document show the largest sources of unintentional release of microplastics into the environment in the EU as follows - based on the highest estimate in each case:

-

Paints (863,000 tons/year): 25% of this relates to abrasion from ships

-

Tire abrasion (540,000): 55% of which concerns cars

-

Pellets (184,290)

-

Textiles and geotextiles through washing and use (80,828)

Unintentional release of microplastics, such as packaging waste that has degraded after being littered in the environment, also make up a sizeable proportion of the total amount. In contrast to colors or the abrasion of car tires, however, this proportion can be reduced through correct waste collection and recycling with an already established solution. To achieve this, ALPLA invests in the expansion of recycling worldwide every year.

How ALPLA Is Reducing Microplastic Pollution

Understanding the origin and impact of microplastics is crucial to developing effective strategies to reduce their presence in the environment. By raising awareness and promoting sustainable practices, ALPLA is helping to curb the spread of these tiny but widespread pollutants.

Do PET bottles contain microplastics?

Numerous studies have investigated whether PET bottles shed microplastics into the beverage they contain. Results show that properly manufactured and stored PET bottles are not a significant source of microplastic exposure for consumers. ALPLA follows strict manufacturing and quality standards to ensure product safety. Additionally, our bottles are designed for recyclability and made from high-purity materials that resist degradation.

Microplastics explained: your questions answered

Microplastics are a serious hazard in particular for the marine ecosystem. And it is not just an issue of marine pollution with a material which is extremely durable and which takes hundreds of years to be broken down. The impact on marine organisms such as seals, fish and mussels, which ingest microplastics passively or via their food, is also a problem. According to an article on nature.com, perhaps the simplest form of damage, at least with regard to marine organisms, could be organisms swallowing microplastics of no nutritional value and therefore not eating enough food to survive.

Based on our food chain, it stands to reason that microplastics can be found in the human body. This has also already been confirmed by recent scientific studies. Research in this area is still in its infancy, so little is known at present about the possible health impacts on humans. Researchers believe that the concentrations of microplastics and nanoplastics in the environment are currently too low to be harmful to human health. Recent articles do show some harmful effects of the plastic particles in mice, but these results cannot be transferred to humans, due to differences in immune system, blood circulation, and microplastics intake. Additionally, even studies which find a statistical correlation between microplastics in the brain and health diseases, are not able to prove a causal relationship.

We need to make a distinction here again between primary and secondary microplastics. Secondary microplastics mostly end up in the oceans due to plastic waste being disposed of incorrectly. Every one of us can play a part in preventing this by collecting plastics and disposing of them correctly. Primary microplastics, meanwhile, are released first and foremost due to the use of products containing plastics and much less so also during production, shipment and recycling. According to the IUCN, primary microplastics find their way into the oceans via four main pathways:

• Direct losses into the ocean, e.g. marine coatings

• Wind dispersion, e.g. particles from car tyre abrasion

• Road run-off, e.g. of road markings

• Wastewater treatment facilities, e.g. fibres from household laundry

The best-known use is their exfoliating effect. Particles smaller than 60 µm are less suitable – the ideal size is around 420 µm. The plastics used are polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP), polyethylene terephthalate (PET), polyamide (PA), polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE, Teflon), polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA), polystyrene (PS), polyurethane (PUR) and various copolymers (UBA microplastics study).

According to a study conducted by the University of Münster which examined 38 different mineral waters in single-use and reusable plastic bottles, glass bottles and beverage cartons, there are traces of microplastics in reusable bottles made of both plastic and glass. Fewer particles were found in single-use bottles and beverage cartons. The study author Darena Schymanski assumes this primarily has something to do with the cleaning needed in the case of reusable bottles. Tap water has the lowest level of microplastics. More information on microplastics in drinking water is available from the WHO.

There are various options here:

• You can identify soluble plastic compounds which are harmful to the environment, for example microplastics in cosmetics, detergents and cleaning products, by looking for names such as acrylate, carbomer, crosspolymer, copolymer and polybutene in lists of ingredients. Tip: There is a ban on soluble plastics being used in certified natural cosmetics and ecological cleaning products.

• Do not use synthetic textiles (polyester, nylon or acrylic): natural fibres such as cotton, wool, silk and linen are biodegradable. In addition, a short washing cycle at a low temperature and a full load of washing is better for synthetic textiles.

• It is also important that plastics be disposed of correctly so that they remain in the loop. Tip: Collect plastic packaging you find in the environment and dispose of it.

• Use public transport more to reduce tyre wear.

Scientists have been studying microplastics for about a decade, but the field is still developing due to the lack of standardized definitions, testing methods, and measurement tools, which complicates comparing results across studies. Microplastics vary in shape, size, and chemical composition, and their behavior differs in various environments such as air, water, soil, or the human body. Consequently, data gaps persist, particularly regarding long-term impacts on ecosystems and human health. Additionally, most tests have been conducted on animals, which presents reasonable differences compared to humans.

While studies have confirmed the presence of microplastics in human blood, mothers' milk, lungs, and even placental tissue, it's not yet clear how long they remain in the body or whether they accumulate over time. The body may be able to eliminate some particles, especially larger ones, through normal biological processes—but smaller particles (especially nanoplastics) may persist longer and potentially cross cell membranes. More research is needed to understand the dynamics of microplastic retention, accumulation, and elimination.

Nanoplastics are even smaller than microplastics - typically under 1 micrometer in size. Because of their size, they can penetrate biological membranes and potentially enter organs and tissues, which makes them an area of increasing concern for both environmental and human health. Research into their behavior and impact is ongoing.

Not necessarily. Many so-called “biodegradable” plastics only break down under specific industrial composting conditions. If they end up in the ocean or landfill, they often degrade very slowly and may still form microplastics during breakdown.

Questions about microplastics? We’re happy to help

We look forward to answering your questions on the topic of microplastics.

Sources:

- IUCN 2017

- Definition microplastics ECHA

- Microplastics in drinking water (WHO)

- Microplastics - Plastics Paradox By Chris DeArmitt

- Setting the scene: What are nanoplastics?

- Nanoplastic should be better understood | Nature Nanotechnology

- Microplastics are everywhere – but are they harmful?

- EU action againts microplastics

- Ingested microplastics: Do humans eat one credit card per week? - ScienceDirect

- Bioaccumulation of microplastics in decedent human brains | Nature Medicine